The Geography of Becoming: A Literary Life - Part One

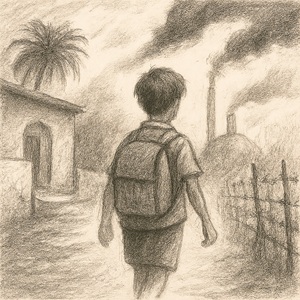

Amandeep Midha is a keen observer of geopolitics- as you must have guessed from his earlier contributions to this magazine. In the present essay, he turns inward - the first part of his memoir of an eventful life - reveals a different aspect of his brilliance. Amandeep grew up in Abohar, a town in Punjab and later went to Amritsar for his college. It is Amandeep, born and brought up in terror-ridden Punjab in 1980s and 1990s - wandering in what he calls 'the geography of fear.' I leave you with Amandeep as he shares how a boy traumatized by violence and terror all around him bears the scar when he grows up and how his childhood memories shape his worldview when he interprets things even in perfectly calm surroundings.

The Geography of Becoming: A Literary Life - Part One

Punjab: The Cartography of Childhood Terror

Amandeep Midha

How books and culture became compasses through the landscapes of trauma, transformation, and transcendence

On the night of March 7, 1990, in Abohar, Punjab, I learned that childhood could be measured not in birthdays but in the intervals between bomb blasts. Barely at eleven, I discovered that some silences are louder than screams: the kind that follows gunfire, when an entire town holds its breath and tallies the living.

Terror, I came to understand, operates on multiple frequencies. There's the sharp, immediate violence, the crack of gunfire that shatters windows and dreams alike. But there's also the slow violence of anticipation, the way a child's imagination gets conscripted into service, constantly calculating danger, measuring the distance between safety and catastrophe. When your regular home electrician transforms from a familiar face into a newspaper headline, first picture of his body in newspaper with blown off leg, then his obituary, you learn that mortality announces itself in the most mundane ways.

Around those years, my mother got news from her best friend in the town of Barnala that her teenage son had been shot dead while attending a ‘Shakha’ . I travelled with my mother and aunt the next early morning, packed into a crowded train under the uneasy hum of fear. The air itself felt volatile, as if terror could strike even there, in the dark rhythm of wheels against the tracks. Yet amid that atmosphere of dread, human empathy had quietly set the priority life must go on, grief must be met. My mother had to see her dearest friend from her own student days, to hug and console her, to bear witness. The sight of that friend, collapsed in her doorway, clutching a faded photograph became one of those images that remain etched in the mind’s inner geography, a permanent landmark of loss.

Also in those days, I remember meeting a school classmate I hadn’t seen for seven months. He had come back to school after recovering from fourteen shrapnel wounds from a blast. Fourteen!! As the number sounded almost impossible. His gait was slower, his smile uncertain, but his eyes still carried that flicker of a child who wanted to belong again and he was still describing as fun and talkative he always was. I remember wondering, should I be grateful? It could have been me. That realization that randomness could decide who lived and who didn’t, was the moment innocence evaporated completely.

Even in 1994, when newspapers and politicians had declared that terrorism was “over,” death still moved through everyday life like an uninvited guest who had learned the habit of staying. One of my mother’s staff, a well to do, and bit flamboyant teacher reporting to her, lost his son, who was shot in the head over a petty college quarrel. Violence had merely changed its vocabulary, migrating from ideology to ego, from extremism to student politics. Death was omnipresent, first wrapped in slogans, later dressed in casual rivalry, but always asserting its dominion.

I was already a little rebel in the family with my inclinations, having chosen science and mathematics after high school, a decision that came crushing to my mother, who, as always with her high empathy, had wanted me to be a medical doctor, while my aunt hoped I would aim for the civil services (IAS). For some reason, I picked subjects where their aspirations did not align, yet they fully supported me despite how miserably I experienced an academic knee-drop in the two years after high school.

Terrorism was probably over, but trauma had shaped itself into physics and mathematics, into complex problems that became daily companions. Early mornings brought tuition, full days were spent in college, and evenings carried two more tuition sessions, exhaustion became a constant, yet knowledge rarely moved forward. Parental comparisons, the looming pressure of entrance exams, and constant reminders of what I “should” achieve weighed heavily. Chemistry was the only subject where I somewhat flourished; in others, I felt myself floundering. And yet, as puberty developed its masculine curiosities, I found a fascination with metallurgy, the alchemy of transforming ores into metals, smelting, shaping, and experimenting. Yes, I realized with growing certainty that I wanted to be a Metallurgical Engineer.

Around 1995, when I secured my engineering entrance rank, somewhere around 2000, my parents’ relief was tempered by fear. Punjab had only about 1,500 engineering seats then, and the idea of sending me far away filled them with anxiety. Every well-wisher became a prophet of caution: Don’t send him too far; college ragging is brutal; the world outside isn’t safe. Beneath those warnings lay a deeper truth : A society still recovering from trauma, where safety felt more valuable than opportunity. Fear, by then, had become our family’s unspoken curriculum shaping every decision, even the pursuit of education.

It was only much later, when I began to understand India’s educational geography, that the disparity became glaring. Comparing the numbers of 1995, one state is Punjab, with 1,500 engineering seats, and another Karnataka with 35,000. That single statistic, simple yet damning, revealed a truth that haunted me: if Punjab had built pathways for employable youth, perhaps the soil wouldn’t have been so fertile for extremism. Unemployment, disillusionment, and pride, those combustible ingredients of militancy, might have found safer outlets in laboratories instead of in violence.

Given this, I applied for different courseware within Punjab, as my parents did not want to send me far to study Metallurgical Engineering. Why not Agriculture at Punjab Agricultural University, Ludhiana? Or why not the new Computers program at Khalsa College, Amritsar? I actually applied to only these two courses. A week later, the application form from Ludhiana came back: my form had arrived a day after the final submission date. Perhaps there were not many takers for the Computers course, because admission landed me home within a fortnight. It was not joyous, but it was something to pursue next.

It would be my first time truly away from home, Abohar, and given how I had been raised, with a constellation of fears, anxieties, and traumas, settling into the first year in Amritsar was not easy. The college hostel where I stayed had once been a hotbed of Sikh extremism. Seniors casually mentioned which known terrorists had lived in which rooms just a few years prior, and the campus itself had witnessed police shootouts and encounters. Sure, I was not new to such news, but living in that space, hearing those stories firsthand, made the history of fear visceral.

The hostel itself smelled of damp blankets, stale kitchen fried oil smell from the canteen, and the faint green campus till horizon. The corridors echoed with history much older than terrorism came to Punjab, as Khalsa college was built in the 19th century, were slamming doors and the low murmur of voices, some friendly, some carrying the same undertones of suspicion I had grown up with. One evening, while unpacking my modest trunk, a senior leaned over from the bed opposite and said casually, “This room? Last year, they found a few Asla (pack of pistols) tucked behind the locker.” I laughed, but the laugh sounded hollow even to me. Everything I touched seemed weighted by history.

Classes were another world. Computers were still rare in Punjab, and our lab had machines that clattered like ancient typewriters - intel 386 and new ones were 486 some with PC-DOS and some with MS-DOS, really those days at least Microsoft and IBM were equal rivals in operating systems. The computer lab had Air conditioning, a new experience for me to enjoy but often get a running nose as well. I found comfort in numbers and logic, even when my body ached from exhaustion, I must say the walk in the lush green campus from one classroom to another was refreshing enough.

Amritsar opened up to me some food innovations especially for someone like me who always saw only a particular way of cooking and a particular way of drinks preparations, . A sweet lime juice (Shikanji) with slices of ripe banana, was my first such experience in the college Canteen. Meals otherwise were a mix making me remember home enough: buttery parathas, spicy liquid dals, strong chai, and the occasional curiosity-driven experimentation with packaged snacks. Conversations often revolved around grades, exams, and whispers of who had once carried weapons, who had survived encounters, and which rooms were “haunted” by past violence. I learned quickly that history lingered not just in textbooks but in the very walls around me.

Yet amidst all this, a strange form of freedom emerged. For the first time, I made small decisions without my mother or aunt hovering: when to sleep, what to eat, whom to sit with in the lab. Fear had not disappeared, but autonomy gave it a frame I could navigate. I became acutely aware of how trauma shaped perception, every sudden shout, every clatter of a door, triggered echoes of the past, yet I could also remind myself: I am here, I am playfully learning, I am moving forward whatever wherever

Despite all this, I often chickened out. Some days, the campus felt too haunted, the walls too heavy with past violence, and I took the bus back to Abohar, skipping lectures just to be home for a while. I hadn’t really built friends yet, and the isolation amplified every echo of fear. My mother was deeply accepting of my fragility, allowing me to retreat without judgment. My aunt, however, took action: she made plans to spend a few months in Amritsar herself, or share the duty with my mother, to help me settle. Over the second year, they rotated their stays, easing my transition into independent life.

On February 14, 1995, I got my first personal computer on Valentine’s day, a powerful very expensive Pentium machine that I made my parents spend money on, but it felt like a gateway to a modern world I hadn’t yet fully grasped. I didn’t know it at the time, but the phrase “Going All In” would soon come to define this chapter of my upbringing: my mother and aunt were living it daily, fully committed to ensuring I could navigate the world beyond Abohar. The second year brought more assurance; I lost 15 kilograms walking every day across the campus and to the accommodation a few kilometers away, under their watchful rotation. Gradually, I began to make connections, two friends, one Sikh, one Jain, both locals; and life started to feel relatively peaceful and established. Having my own computer meant I could take extra elective books, learn programming at my own pace, and perhaps even pull ahead of my batchmates.

That very year, marked by anxiety, study, and tentative independence, became a microcosm of my Punjab experience: history, trauma, fear, and human adaptability all coexisting. It was my first real test of self-construction, of navigating a world where danger had once defined normalcy, but where the future could still be charted in numbers & codes, if not in smelted metals.

Yet even within this geography of fear, I witnessed the strange topology of human contradictions. The same Sikh community that Abohar viewed with suspicion welcomed me in Lakhewali with halwa prasad and embraces that spoke of unconditional love. The Gurudwaras became spaces where the harsh mathematics of identity politics dissolved into simple human arithmetic: one person extending kindness to another. This early exposure to paradox, how the same people could embody both threat and tenderness, depending entirely on the angle of your approach, became my first lesson in the complexity of human nature.

The Psychology of Parallel Compassions

I also witnessed courage wearing two different faces in the women who raised me. My aunt wielded compassion like a weapon, marching into police stations to force the filing of ignored complaints, battling school administrators who tried to quietly deny admission to two Muslim children. Her justice was performative, combative, designed to bend systems that preferred to remain unbent. My mother's compassion, by contrast, was atmospheric and a quiet embrace that enveloped without confronting, healing without declaring war.

Together, they taught me that righteousness has multiple expressions, that standing up for others can take forms as different as a whisper and a war cry. This duality would echo through my life: the recognition that there are always multiple ways to be moral, multiple ways to resist, multiple ways to care.

Books as Escape Pods from Reality

In this landscape of uncertainty, my aunt offered me a peculiar kind of salvation: the choice between chicken and books. I almost always chose books with titles from the "Vishwa Prasidh" (World Famous) series that became portals to elsewhere. Nearly forty titles by high school's end: journeys through the Bermuda Triangle, expeditions to Everest, expeditions to north and south poles, colonial occupation wars from Vietnam to Falklands war, spy stories, world war battle fronts spanning from Lithuania to Japan, explorations of medicinal herbs and planetary evolution.

These books weren't just entertainment; they were training in alternative realities. When your immediate world contracts to the size of a 7 p.m. curfew, when shop shutters become the period at the end of each day's sentence, imagination becomes an act of resistance. Each book was a small rebellion against the geography that confined us, proof that consciousness could travel even when bodies could not.

Insight: Childhood trauma creates peculiar forms of intelligence. Living through contradiction teaches you that truth is rarely singular, that fear and love can occupy the same psychological space, and that survival often depends on your ability to hold multiple realities simultaneously. The books I consumed weren't just stories, they were evidence that other worlds existed, that the violence outside my door was not the sum total of human possibility.

***********

(Continues)

The next part of this article is also now available here

Amandeep Midha is a technologist, writer, and global speaker with over two decades of experience in digital platforms building, data streaming, and digital transformation. He has contributed thought leadership to Forbes, World Economic Forum, Horasis, and CSR Times, and actively engages in technology policy-making discussions. Based in Copenhagen, Amandeep blends deep technical expertise with a passion for social impact and storytelling.