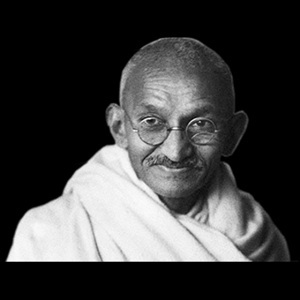

Gandhi as an Idea: When Power Performs, and Conscience Watches

30th January offers an apt occasion to assess how far Godse succeeded in wresting away Gandhi from us on that fateful day in 1948. Is there still some Gandhi left at the core of our society, or has Nathuram snatched him away completely after 77 years since his sinister attempt stripped away Gandhi's physical form? Here is another profound piece by K.G. Sharma, who has also included an author's note at the end.

Gandhi as an Idea: When Power Performs and Conscience Watches

Krishan Gopal Sharma

As politics worldwide slides into spectacle, coercion, and moral theatre, Mahatma Gandhi returns not as nostalgia, but as indictment. His idea—of restraint, moral communication, and accountability—may be the last civilising language for a world adrift toward historical repetition.

There is no alternative. When power normalises coercion, majorities mistake dominance for legitimacy, and silence passes as prudence, societies exhaust their moral vocabulary. In such moments, Gandhian restraint, Nehru’s pluralism, and Mandela’s all-encompassing ethics are not lofty ideals—they are the last bulwarks against civilisational regression. Strip them away, and politics shrinks to muscle, identity to weapon, democracy to mere arithmetic. History shows where that road ends. The question is no longer their relevance, but whether the world can survive without them.

History rarely announces collapse. It rehearses it—through applause, silence, ceremony, and adjustment. Long before force normalises, societies acclimate to symbols supplanting substance, performance eclipsing principle. By the time coercion stands openly defended, conscience has already softened. It is then that Gandhi returns—not as statue or slogan, but as a disturbing question.

Gandhi survives because the conditions he confronted have returned in altered form. Militarisation, unilateral decision-making, suppression of dissent and moral exceptionalism are again being defended as efficiency, strength or national necessity. What Gandhi offers is not an ideology to compete with these forces, but a method that exposes their ethical emptiness. He reminds us that power without restraint corrodes not only its victims, but the society that applauds it.

A Lesson History Keeps Teaching—and Power Keeps Ignoring

The First World War did not begin as madness. It began as confidence — confidence in alliances, in militaries, in decisive action. The Second World War followed when humiliation, grievance and force replaced dialogue altogether. Each catastrophe was justified at the time as unavoidable. History later revealed something simpler: the failure of restraint.

Gandhi grasped this early. In 1946–47, as communal violence consumed the subcontinent, he refused office, refused authority, and walked instead into riot-torn neighbourhoods with no protection but moral appeal. At a moment when power could have been seized, he chose to reduce himself. That act remains one of the most radical political gestures of the modern age. It demonstrated that legitimacy does not always flow from institutions downward; sometimes it rises from conscience upward.

When Power Wears Piety

Gandhi was deeply religious, yet uncompromisingly wary of religion entering politics as spectacle. For him, faith was a private discipline of humility, not a public credential of authority. When political leaders perform priestly roles, preside over rituals, or embody sacred symbolism while wielding state power, the danger is not devotion—it is sanctification.

Once power acquires a sacred aura, dissent becomes heresy. Criticism is no longer disagreement; it is moral deviance. Gandhi feared precisely this fusion. He warned that when religion stops restraining power and begins adorning it, both religion and democracy are diminished. Symbolism without sacrifice, ritual without restraint—these were, to him, signs of moral inversion.

Peace as Performance, Not Practice

A similar inversion is visible in how peace is discussed today. Gandhi was nominated several times for the Nobel Peace Prize and never received it. He never sought it, nor did he lament its absence. Peace, for him, was not an outcome to be claimed but a discipline to be practised—daily, consistently, and often invisibly.

The idea that peace can be demanded, advertised or claimed while practising coercion, threats or humiliation would have troubled him deeply. Gandhi believed peace was inseparable from means. If fear produces quiet, it is not peace; it is suspended violence. Recognition pursued without restraint reveals not achievement, but misunderstanding.

Democracy Hollowed from Within

The present danger is not confined to overt authoritarianism. It is unfolding within electoral democracies as well. Under majoritarian systems, procedural victory is increasingly mistaken for moral legitimacy. Elections become shields. Dissent is reframed as disruption. Silence is rewarded as stability.

Gandhi rejected this arithmetic view of democracy outright. For him, democracy was a living moral contract, not a periodic transaction. A state that wins elections but punishes dissent may be legal, yet unjust. When citizens accept this trade-off, democracy is not abolished—it is emptied of meaning, gradually and with popular consent.

The Spectator Society

Perhaps the most uncomfortable question Gandhi would ask today is not of leaders, but of societies.

What happens when citizens become spectators to moral erosion?

When coercion is excused as efficiency?

When spectacle replaces accountability?

When watching feels safer than questioning?

History suggests that societies rarely fall because of one tyrant alone. They falter when large numbers decide that neutrality is wisdom, that silence is prudence, and that adjustment is survival. Gandhi believed that the gravest moral failure was not oppression itself, but the quiet acclimatisation to it.

Moral Communication: The Last Civilising Language

At the core of Gandhian thought lies moral communication — the refusal to dehumanise even while resisting, the insistence on dialogue even under provocation, and the discipline to oppose without becoming what one opposes. This form of communication does not eliminate conflict; it civilises it.

When states speak only the language of force—raids, sanctions, threats, spectacles—trust collapses. Institutions weaken. Treaties become conditional. History begins to repeat itself, not dramatically at first, but predictably. Gandhi’s method sought to interrupt this cycle by reintroducing restraint where power preferred speed.

Why Gandhi Is Resisted Today

This is why Gandhi is not merely forgotten, but actively diluted. His image is celebrated, his method neutralised. His saintliness is praised, his politics dismissed as impractical. In reality, his idea is resisted because it demands something modern politics resents: self-discipline by the powerful and moral courage by the ordinary.

He offers no shortcuts, no intoxicating slogans, no enemies to dehumanise. He insists that ethics cannot be suspended for convenience. That insistence is profoundly inconvenient in an age addicted to immediacy and dominance.

Conclusion: The Inconvenient Light

Gandhi does not console societies; he interrogates them. He reminds us that strength without restraint is not strength, that peace without ethics is illusion, and that democracy without conscience is performance.

Above all, he unsettles the comfortable belief that spectatorship is innocence. Watching injustice without resistance is itself a form of participation. History does not judge only those who wield power; it also judges those who looked away.

The choice before the world is not between idealism and realism. It is between moral effort and historical repetition. Gandhi, as an idea, remains the last inconvenient light—refusing to flatter power, unwilling to soothe society, and persistent in its warning: civilisation survives not by celebrating force, but by disciplining it.

***********

Author’s Note

I write this essay with a tremor in my hand and a weight in my chest, for what I describe is no longer abstract—it is daily life. We are living in a world, and in an India, where the languages of conscience are being replaced by the languages of power: spectacle, coercion, identity as weapon, silence as survival.

It is a bitter paradox: the very ideals that once demanded courage—Gandhian restraint, ethical pluralism, moral accountability—are now admired only in memory, while their opposites—absolutism, grievance, violent certainty—creep into the centre of public life with alarming ease. History, patient and impartial, waits. It is already rehearsing the tragedies we refuse to name, even as we clap, adjust, or avert our gaze.

I do not know if Gandhian thought will survive this age. I do know that voices like Godse’s—rooted in grievance, sanctified by fear, energised by spectacle—have never been more tempting. To witness this moral tug-of-war without anguish is impossible; to remain silent is complicity.

This essay is born of that anguish. It is written to puncture comfort, to disturb the calm, to insist that conscience is not a luxury but a responsibility. If nothing else, it is a record of unease: that the battle between restraint and rage, dialogue and domination, ethics and ambition, continues—and that every citizen, every spectator, is already a participant.

History does not spare those who watch. And neither should we.

The author is a retired officer of the Indian Information Service and a former Editor-in-Chief of DD News and AIR News (Akashvani), India’s national broadcasters. He has also served as an international media consultant with UNICEF in Nigeria and continues to write on politics, media and ethics.